Joan of Arc

Kasteelvertrek met Jeanne d’Arc, Paul (graveur), after Richard, 1750 – 1850, etching RP-P-1909-1

Joan of Arc was a 15th-century French military leader who fought against English troops during the Hundred Years’ War and broke the siege of Orléans. In 1429, she convinced Charles VII to be crowned as the King of France, signalling the beginning of France as a nation-state. After she was captured by Burgundian troops, who were French allies of the English, Charles refused to pay her ransom. Many believe this was because he felt threatened by her position as the leader of a peasant army. Joan was tried for heresy by the English and burned at the stake in 1431, at the age of around nineteen.

Joan was only canonised by the Roman Catholic Church in 1920. She is the most recent saint in this exhibition, and yet she has possibly the most complex legacy. Joan is remembered as a patriot, an epileptic, a crossdresser and countless other identities. Her modern followers range from far-right populists to transgender lesbians.

A National Treasure

Fotoreproductie van (vermoedelijk) een prent naar een schilderij van Jean-Jacques Scherrer, voorstellend de terugkeer van Jeanne d’Arc in Orléans, Neurdein Frères (attributed to), after anonymous, after Jean Jacques Scherrer, c. 1880 – c. 1900, albumen print RP-F-2004-283-35

Holding a flag aloft, Joan rallies the people around her in this piece. Joan’s passionate defence of France, at a time when the nation still lacked a unified identity, has made her a hero to many French nationalists in the years since her death. Today, Joan’s image is most notoriously used by Rassemblement National (National Rally), a far-right political party in France. Every May Day, the party’s supporters march to a statue of Joan on the Rue de Rivoli in Paris. The party’s adoption of Joan as a figurehead has been controversial, as they champion a very narrow, traditional, view of the ideal French citizen. Many French people believe that Joan’s image shouldn’t be politicised at all.

Joan’s Visions

Reproductie van Jeanne d’Arc door Eugène Romain Thirion, Charles Michelez, after Eugène Romain Thirion, c. 1871 – in or before 1876, paper RP-F-F25216-AK

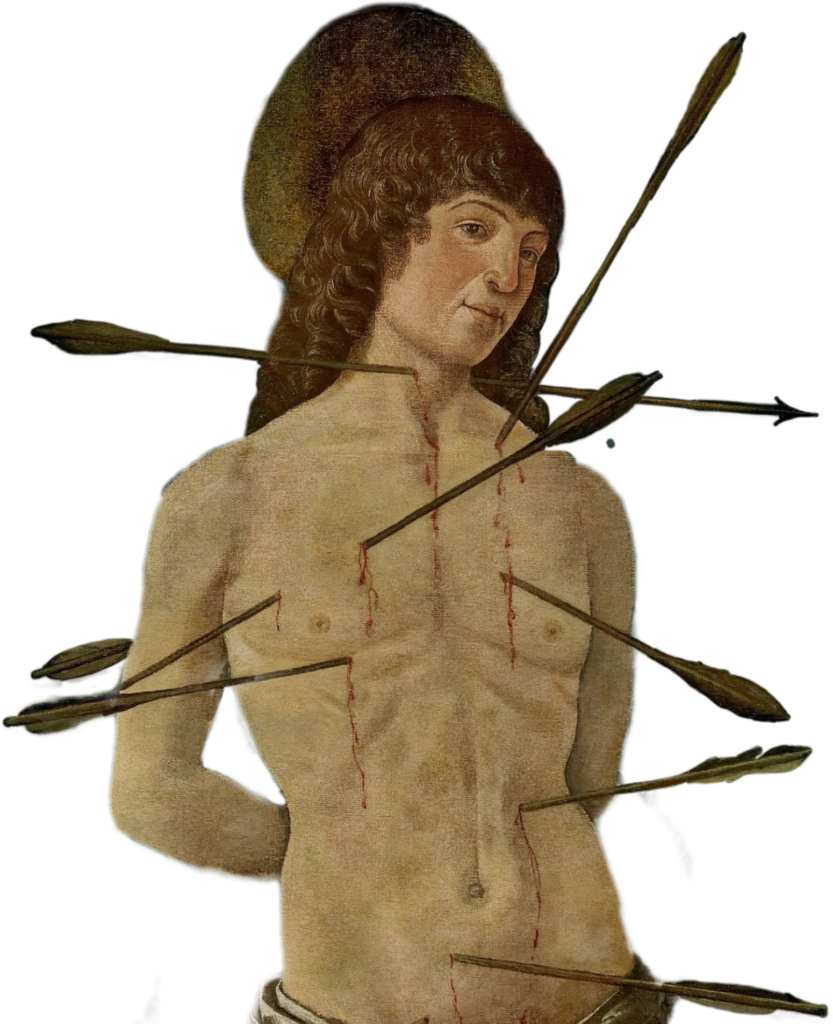

During her Trial of Condemnation, Joan claimed that she often heard the voices of the Archangel Michael, Saint Catherine and Saint Margaret. The voices urged her to defend France against England’s forces. These auditory hallucinations were usually accompanied by a bright light or the faces of the saints.

Joan’s wide-eyed, fervent gaze in this image conveys her absolute belief in her mission from God. As we have turned from religion to science for answers, we’ve developed an affection for diagnosis. Modern neurologists have suggested that Joan may have had schizophrenia or epilepsy. Now that our society is more secular, Joan can escape the accusations of witchcraft that were made against her back then. However, she loses her divinity in the trade.

A Man’s Dress

Jeanne d’Arc wordt door soldaten gevangen en meegevoerd, Adolphe Alexandre Dillens, 1851, etching RP-P-BI-7077

One thing about Joan that stands out to many people is her gender expression. Because Joan cut her hair short and wore men’s armour, her Burgundian captors referred to her as hommasse, an insult meaning ‘man-woman’ or masculine woman. She was ultimately executed for ‘relapsing’ into men’s clothing, after agreeing to wear dresses for a brief time whilst in prison. Joan’s gender variance has been highlighted by scholars working to reveal queer histories. It has also been celebrated in the arts, such as in I, Joan, a 2022 production at the Globe Theatre. The play received online criticism from TERFs (trans-exclusionary radical feminists) for portraying Joan as nonbinary.

‘For nothing in the world will I swear not to arm myself and put on a man’s dress’ – Joan of Arc