How Artistic Representations of Families Have Been Shaped at the Yale Center for British Art.

‘Say Cheese!’

Love it or hate it, we’ve all heard it! Humans have been proverbially saying ‘cheese’ for over a millennium and with the ability to record and display your immediate family becoming commonplace, it seems we’ll be saying ‘cheese’ for many more years to come!

This exhibition brings together 18th and 19th century paintings, sketches, and ink drawings to reveal the dominant perception of family life during this period. Images from Tate Britain and the Yale University Art Gallery will be shown alongside work from the Yale Center for British Art, these works were acquired using the Paul Mellon Credit Line or through Paul Mellon’s bequest to the University of Yale.

Nowadays, it is easy to snap a photo on your iPhone and upload it to Facebook under an album titled ‘Family’. How much thought goes into this decision? How many photos do you take before selecting ‘the one’? This album has been curated to portray the so-called ‘perfect family’, your family, in the way that you understand ‘perfection’.

Likewise, Paul Mellon, an avid collector of 18th and 19th century British Art curated a collection with a narrow view of the 18th and 19th century family. This collection is based entirely on his personal preference and taste. These pictures also reflect the 18th and 19th century understanding of the ‘perfect family’, a family who adheres to tradition.

Split into three sections, the exhibition is structured as follows:

- A Big Group: A Family or A Social Occasion explores the function of group outings and activities within family life.

- ‘A Place for Everything and Everything in Its Place’: Inter-Family Relations and Power Dynamics investigates the domestic sphere and the rigid roles and expectations at play within the family structure.

- A Wider View of the Family: Presenting the Under-represented Groups, focuses on the family structures that have been depicted infrequently within the collection.

A Big Group: A Family or A Social Occasion?

A Family Group Around a Piano

c.1812-1815

George Chinnery

Pen and Black Ink on Cream Wove Paper

This pencil drawing depicts a scene of a family sitting in front of the piano for family activities. The title of the drawing reflects that in the early 19th century in England, the concept of the size of families was about 6 people or more, which is different from our current family composition.

Portrait of a Family, Traditionally Known as the Swaine Family of Fencroft Cambridgeshire.

1749

Arthur Devis

Oil on Canvas

This painting represents most of the 18th-century family leisure activities in the Paul Mellon Collection. Most of them are fishing by the lake or in their own estate. From the clothes and scenery we know most of the family activities will not be far from the estate. Male on the right of the piece seems separating from the family portraits as the father role leads the family group.

Portrait of a Family

1735

William Hogarth

Oil on Canvas

The painting illustrated a 18th century social event that was held in an aristocratic house. People in the family are well dressed and focused on the man speaking. The man in the centre is looking at the man on the right sofa who was petting his dog. The women seemed to only be accompanying men on social occasions and the family group appeared to consist of only adults.

The Rev. and Mrs. Henry Palmer with their six younger children at Withcote Hall, Near Oakham, Leicestershire

1838

John Ferneley

Oil on canvas

In 19th century, the state basically has no control over fertility, a rich family has many children which is a normal phenomenon and a big family usually consists of 6 people or more. Poor family who cannot afford will have lesser children that the number of family depends on family economic strength as well. As the core of the family, men usually show off and pride of they have a big family.

‘A Place for Everything and Everything in Its Place’: Inter-Family Relations and Power Dynamics

First Class

Abraham Solomon

1855

Oil on Panel

Courtship began with conversation. In this image, a naval officer engages a young woman in conversation, only to be intercepted by her father. Young women were not permitted to entertain male company without a chaperone. Often, male relatives would assume this role. In a previous version, Solomon depicted the officer speaking to the young woman flirtatiously whilst the father slept soundly.

The Proposal

Nathaniel Dance

1735-1811

Watercolour and Chalk on Paper

Resting on his knees, an older gentleman proposes to a reluctant younger woman. Marrying men who were older became commonplace and even encouraged in 19th century England. Older men were seen as ‘prizes’ as they were more likely to be financially well-off, or at least stable, and marrying ‘up’ served to reinforce the ‘natural’ hierarchy between the sexes.

Second Class – The Parting

Abraham Solomon

1855

Oil on Panel

Working class families in Victorian England often lived in small quarters. This fostered a tight bond between family members, particularly the mother and child. Young boys left home between the ages of 10 and 14 to begin work. This young boy is departing for Australia, his mother woefully clutches his hand.

Two Girls Playing / Tea Party

Robert Barnes

1840-1895

Wood Graving with Watercolour on Paper

Upper-class Victorian children were confined to the Nursery. Outdoor play was limited and contact with their parents almost non-existent. Because of this, their parents were given the moniker ‘glamourous guests’ and raising ‘accomplished’ young women fell to the Nanny. Pastimes such as the pictured Tea Party were firm favourites as these prepared the young girls for life beyond the home by placing formal skills from etiquette to preparing food and drink at the forefront of play.

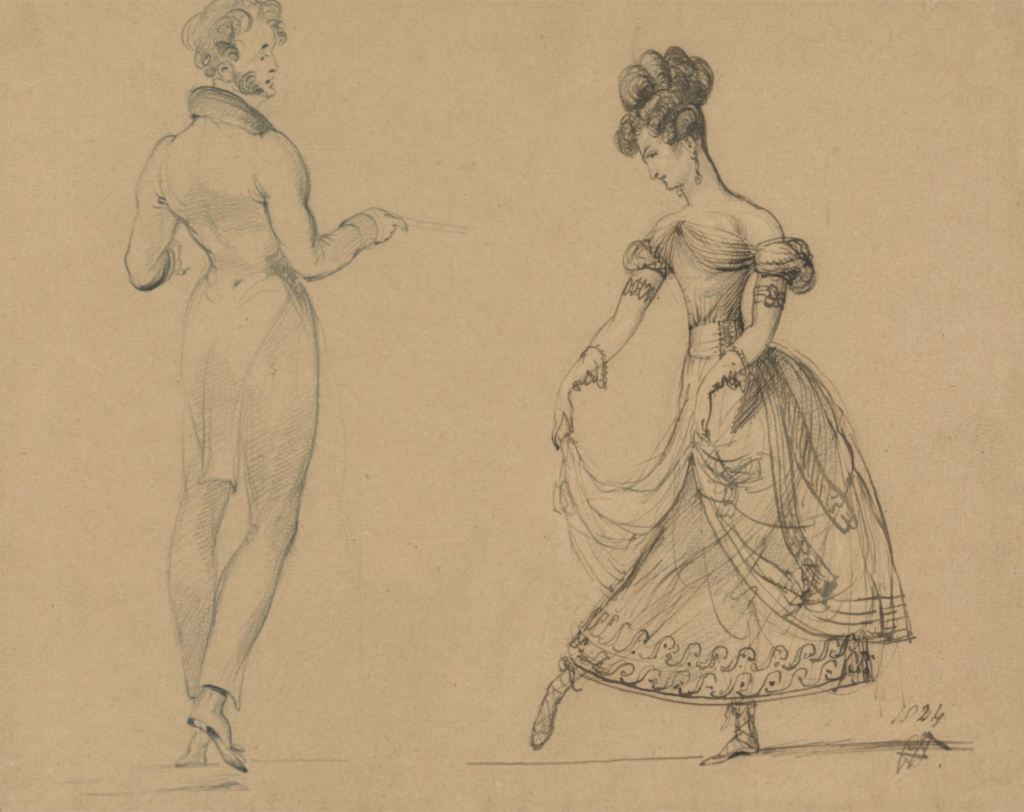

A Minuet

Sir George Hayter

1824

Pen, Ink and Graphite on Paper

Here is a young man engaging a young lady in a dance. However, asking her to dance with him two or three more times would be improper. If he did ask, it would have been the woman’s responsibility to refuse. If she did not, her reputation would be in ruins, the fault entirely her own. Even engaged couples were not permitted to dance together all night, it was considered poor taste!

A Wider View of the Family: Presenting Under-Represented Groups

The Spoiled Child, Scene V

1802

Lewis Vaslet

Watercolour with Black Ink and Grey Wash over Graphite on Cream Wove Paper.

The spoilt child is a young girl, depicted as threatening, having vandalised a drawing room. This is an unusual depiction from the collection, as 18th century women are usually shown to be demure and impeccably behaved, having been taught etiquette throughout their lives.

The Dead Soldier

1789

Joseph Wright of Derby

Oil on Canvas

Crouched beside the dead Solider is his presumed wife and child. The Soldier will have been a source of stability for the family, his income would have been all they had due to roles in the 18th century. The death of a husband gave women a new place in society, widows were free to live without a new husband, if they chose. They were offered a sense of autonomy which was rare for this time.

‘The Awakening Conscious’

1853

William Holman Hunt

Oil on Canvas

On Loan from Tate Britain

A woman is depicted rising out of her lover’s lap, her lack of wedding ring tells us she is unmarried. She is leaning towards the brightly lit garden and this act is symbolic of her ‘awakening conscious’, she’s searching for redemption. This painting depicts a woman who realises she has a choice of her role within society.

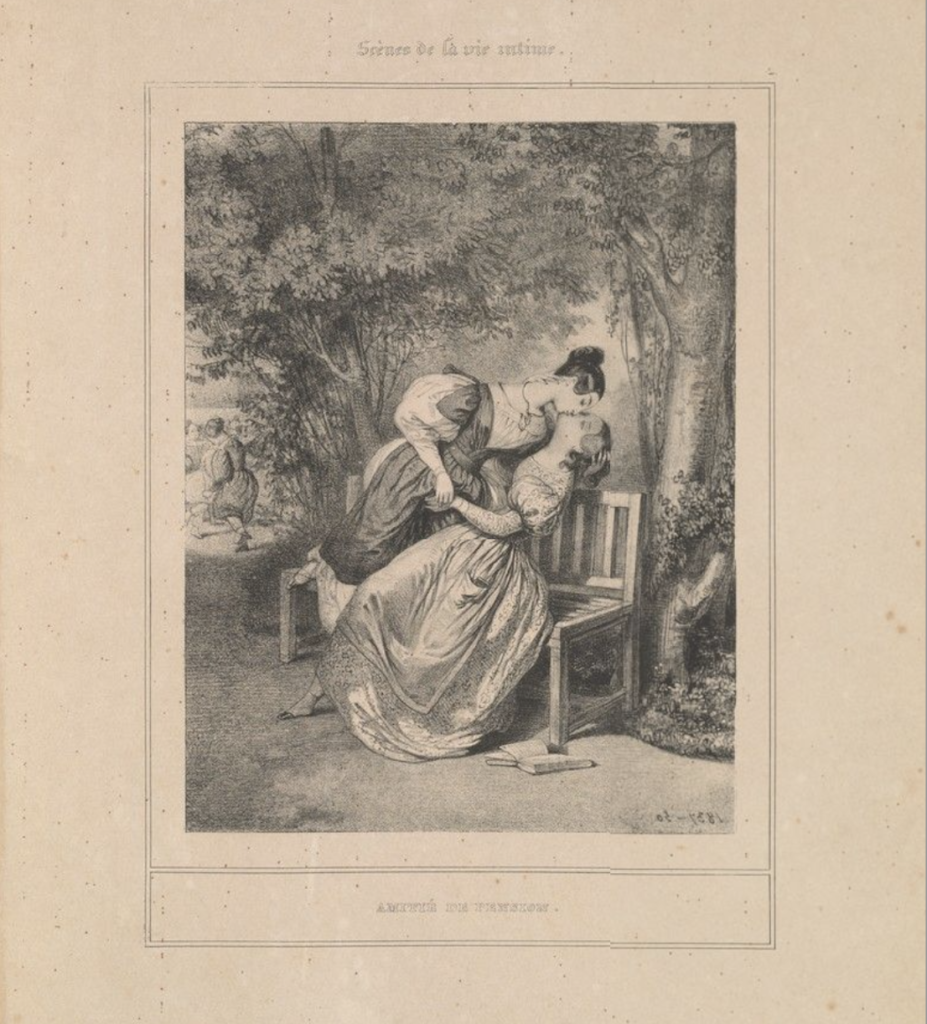

Amitie de Pension, from the series Scenes de La Vie Intime

ca. 1837

Paul Gavarni

Lithograph

On Loan from Yale University Art Gallery

Two women are seen kissing on a bench, an act that isn’t shocking now, but at the time would have been astonishing and perceived as immoral. This lithograph depicts women with their own autonomy, they have freedom of choice within their relationship because there is no ‘natural’ hierarchy, instead they are both equal and chose to find a family in one another.

*End of Exhibition*