Introduction

The true sense of lace emerged in the 15th Century; the following Century marked an increasing popularity of this intricate fabric in Western Europe, and gradually spread around the world. By the 16th Century, lace had become an accessory for the upper classes in Europe, due to its complex and intricate craftsmanship, and a delicate, elegant texture.

But how did lace come to be? Ladies would often spend their leisure time engaging in activities such as music, painting, and knitting to pass the time; and thus the art of lace-making was born. As a practice that required painstaking attention to detail, it was naturally considered a gendered hobby; women were expected to exhibit the same patience and control needed to make lace as was needed to care for children. Average, lower class, family-rearing women were the artists behind the creations.

Over time, with the widespread popularity of lace, demand for large quantities of the fabric increased; and it forced the outsourcing of the labour of our mothers to machines during the Industrial Revolution in the 1830s. Both before and after the emergence of machinery, making lace meant difficult working conditions for the working class seamstresses in lace factories, or netting by hand. Many people who sparked this faceless textile revolution and worked long and difficult hours making the sophisticated fabric have remained unnamed and forgotten.

We encourage visitors to keep the uneven power dynamics in mind as they explore our exhibit.

The Makers

Lace Sample, ca. 1845

William Henry Fox Talbot, 1800–1877

The spread of pattern books had a profound impact on the development of lace in the 16th Century. By the late 15th Century, pattern books had already been applied to the production of embroidery and lace in Germany, and in the following centuries, an increasing number of pattern books were produced, with designs applied to crochet, embroidery, and eventually lace.

Before the Industrial Revolution in the 18th Century, handmade lace was produced in simple home workshops to supply the upper class fashion industry. Sophisticated designs required extensively lengthy processes, and often left lacemakers exhausted after long hours.

The Seated Sleeping Seamstress, undated

Print made by Gerard Valck, 1651/2–1726,

after Michiel van Musscher, 1645–1705

Woman Sewing, undated

Print made by Abraham Blooteling, 1640–1690

How are these women represented as labourers? Does their environment, their facial expressions, or even the method in which they are depicted impact how their craft is viewed?

London Cries: A Lace Seller

circa 1759

Paul Sandby, 1731–1809

The 18th century in London faced rapid economic growth, especially in terms of trade and manufacturing. Lace, part of the exponentially growing textile industry, provided business prospects for merchants and job opportunities for the working class.

‘The makers’ remain a nameless, faceless working force. Even the pieces in which they are documented refrain from disclosing their identity and this is exclusively relevant to the depiction of women. This, therefore, creates space for thinking not only about issues revolving around class, but also, gender.

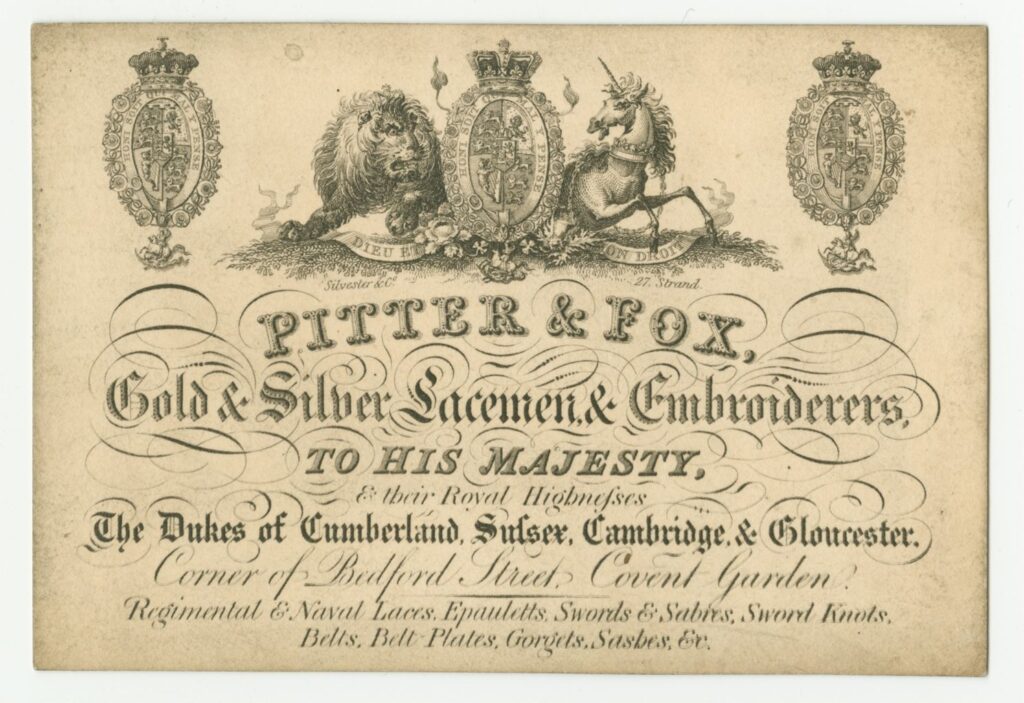

Gold & silver lacement & embroiderers to His Majesty & Their Royal Highnesses the Dukes of Cumberland, Sussex, Cambridge, & Gloucester, ca. 1825

Pitter & Fox

Due to the emergence of lace factories in the 19th century, lace, a part of the textile industry, became a growing business. The making of lace grew into a profitable industry providing space for business to grow around England and the rest of Europe.

Lower class women, therefore, felt the pressing need to abandon lacemaking as a hobby to be done in free time and, instead, industrialise it by conforming to economic demands.

Lace Factories, Study 5, Calais, France #4/45, 1998 © Michael Kenna

Lace Factories, Study 21, Calais, France #4/45, 1998 © Michael Kenna

Lace Factories, Study 36, Calais, France #6/45, 1998 © Michael Kenna

In order to meet the rising demands of the fashion market, high quality lace has been constantly changing its technical and artistic styles. The era of machine produced lace arrived in the first half of the 19th Century and lace factories emerged, primarily in Nottinghamshire in England.

These prints by Michael Kenna give us first-hand insight on what lacemaking in a factory setting was like. As can be seen in Study 21, the intricate nature of the work required not only specific equipment but an abundance of such. The size of the equipment and the building reflect the pursuit of large-scale production needed for a booming industry at the time. However, it is worth noting the dejected atmosphere that can be sensed both from the interior and exterior shots of Study 5 and 36.

Below is an audio of a lace machine. It is difficult to imagine how loud the inside of lace factories would have been, as multiple machines operate simultaneously, creating an overwhelming cacophony of noise.

The Wearers

Elizabeth, Queen of Bohemia, after 1596

Isaac Oliver, ca. 1565–1617

Elizabeth, daughter of King James I of England, was known for her beauty, intellect, and grace, qualities which Oliver captures with delicate precision in this work.

Elizabeth’s portrayal is emphasising her royal stature and dignity. She is depicted wearing an intricate gown adorned with lace, an element symbolising both her high status as the fine lacework framing her collar and cuffs provide an implication of luxury.

We can draw upon the portrayal of Elizabeth, especially in relation to the use of lace, and think about its symbolic meaning.

Meanwhile, what is hidden? Can you think of ways the makers are out of sight symbolically and what it implies in terms of class divide?

Catherine Killigrew, Lady Jermyn, 1614

Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, 1561–1635

Frances Brydges, Lady Chandos, 1579

George Gower, ca. 1538–1596

formerly John Bettes the Younger, died 1616

Renaissance portraits were less about the faces of the sitters but what accompanied them: clothing, jewellery, and landscape. Some would even send off their clothes to the painter so that the detail they wanted could be achieved. Lace, in this context, is shown as a luxury – something to be shown off. However it was only those who could afford it that could do so, with lace-makers themselves never getting the opportunity to wear the articles they made.

Hence, the portraits on display in relation to lace here represent symbolic meanings of wealth, elegance, purity and beauty.

Lace Sample Book

“Image Not Yet Available”, 1930s

Probably made for use by an English retailer, this book contains approximately 300 varying samples of machine lace patterns for various purposes. Included in it is one large hand-made sample, most likely to serve as a standard for the quality hoped to be replicated in machine work. As the context suggests, the industry was keen on preserving the quality of hand-made lace, but yet substituting it by machines.

But as they have closed their doors and digitised their collections, why has the Yale Center for British Art neglected to provide us with an image of this book? Do we still today find ourselves prioritising portraits of the lace wearers over the meticulous work that went into making it?

Conclusion

In the modern age, lace production industries have certainly changed since its heyday. Compared to the 18th Century, production speeds have increased to a point that has never been seen before, and that is, perhaps, something we now take for granted. That is why it remains extremely important for us to be mindful of the clothes we all wear, and the origin of such.

It is important not only in an appreciative sense, but in an ethical one too. With the increased production came an epidemic of fast fashion; the lives of garment makers seemed bleak in the 18th Century, and unfortunately, in some cases, the lives of modern-day garment factory workers remain so.

Going forward, acknowledge where your clothes come from, commit to being a mindful consumer, and, most importantly, appreciate the ones that are secondhand or handmade. Indeed, like many hobbies, handicrafts go in and out of fashion, but they are still prevalent. And, although interest may have dwindled, hand-making lace specifically is still an active handicraft, both as a hobby and as a small business opportunity.

Acknowledgements and Copyright

The exhibition is inspired by the online collection at the Yale Center for British Art, and all the objects used belong to this institution.

Most images come from the public domain and can be found here.

‘Lace Factories, Study 5, Calais, France #4/45, 1998’; ‘Lace Factories, Study 21, Calais, France #4/45, 1998’, and ‘Lace Factories, Study 36, Calais, France #6/45, 1998’ have been used with the Artist’s permission. © Michael Kenna.

This exhibition has been curated by The University of Leeds MA students: Yael Gunter, Roman Manson, Yuting Hu, and Klaudija Bruzaite.